Jan. 18, 2019 — Wyoming’s Department of Health has confirmed another case of plague in a cat, the third in the past 6 months in the state.

No human cases of plague, spread by fleas, have been reported during that time, but public health officials are advising people to practice flea control for their household pets and to take animals who appear sick to the vet immediately.

“Most of the cats had a history of going outside,” says Karl Musgrave, DVM, state public health veterinarian.

They probably were exposed to fleas when outside hunting rodents, he says. With awareness of the symptoms, and prompt treatment, the disease is treatable in pets and humans, he says.

“The cats all lived,” Musgrave says.

What Is Plague, and What Are the Types?

Plague is a serious bacterial infection. It is caused by a germ, Yersinia pestis, that is spread by fleas and cycles naturally among wild rodents, the CDC says.

The most common form is bubonic. It usually happens after the bite of an infected flea.

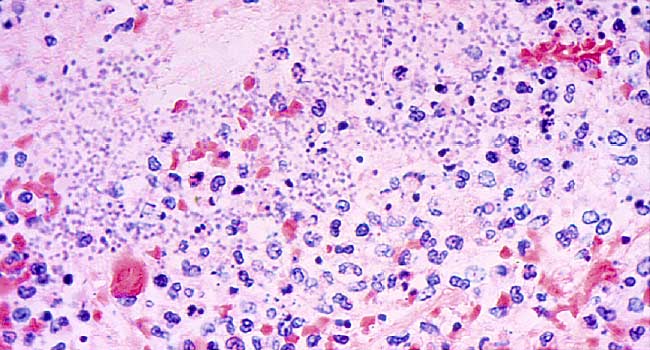

Left untreated, bubonic plague can become the type known as septicemic plague. It happens when the bacteria causing plague multiply in the bloodstream and spread throughout the body.

When the bacteria infect the lungs, it is known as pneumonic plague.

How Is Plague Spread?

According to the CDC, plague in people often happens after a large number of infected rodents die. Then, the hungry infected fleas seek out blood from other hosts, including people and household pets.

People can get plague by being bitten by an infected flea, touching infected animals, or inhaling droplets from the cough of an infected person or animal, the CDC says.

What Are the Symptoms?

Symptoms vary by type. For bubonic, the symptoms in people include swollen, painful lymph nodes, usually in the groin, armpit or neck. Those infected may have fever, extreme exhaustion, chills, and headache. Illness typically happens 1 to 6 days after infection.

Septicemic plague symptoms include high fever, belly pain, exhaustion, and light-headedness.

Symptoms of pneumonic plague include high fever, cough, chills, breathing problems, and coughing up bloody mucus. This form is nearly always fatal if not treated promptly, the CDC says. And it can be tough to tell the difference between this and pneumonia, experts say.

In infected cats, there is often a swelling under the jaw line, Musgrave says. Often, cat owners will tell the vet they are concerned about a big lump around the animal’s jaw, he says. Lack of appetite in cats is another potential warning sign, he says.

Dogs are a bit more resistant to plague, he says, but can get it. “They will stop eating and may have a fever and shortness of breath,” he says.

How Common Is Plague?

Plague has been around since at least the 6th century but first happened in the U.S. in 1900.

Since 2000, about seven cases of human plague have been reported each year, says the CDC.

Plague is common among animals, especially in the Western part of the U.S., says Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security.

“We know that the Western part of the U.S. has a population of rodents with high levels of plague,” he says. “Cats are well known to be able to acquire plague from the rodents they come into contact with.”

How Is It Treated?

They typical treatment is IV antibiotics in a hospital for 7 to 10 days, Adalja says, with the length depending on how severe the illness is.

With the introduction of antibiotics, the fatality rate in the U.S. has dropped to about 11%, the CDC says, citing statistics from 1990 to 2010. Prompt treatment cuts the chance of death.

“Those exposed can also be treated,” says Adalja, who’s also a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “If you have been exposed to plague, in close contact with pneumonic plague, or taking care of an animal that has it, and [say] a flea jumps off, you could be a candidate for post-exposure antibiotics,” he says.

What Is the Best Way to Prevent It?

To prevent plague, the CDC recommends protecting household pets by:

- Treating dogs and cats for fleas regularly

- Keeping pet food in containers that rodents can’t get into

- Taking sick pets to the vet promptly

- Not letting pets out in areas with high rodent populations, such as prairie dog colonies

Other measures:

- Remove excess firewood, trash, and other nesting places near your house.

- Don’t pick up or touch dead animals; wear gloves if you must handle them.

- Report sick or dead animals to your public health department.

- Prevent flea bites by using DEET-containing insect repellents.

- Don’t let your pets sleep with you; doing so raises the risk of you getting plague.

Keeping the risks in perspective — and knowing the importance of prompt treatment and flea protection for pets — is crucial, say Kim Deti, a public information officer for the Wyoming Department of Health.

“This is not the Middle Ages,” she says. “Plague is a treatable disease.”